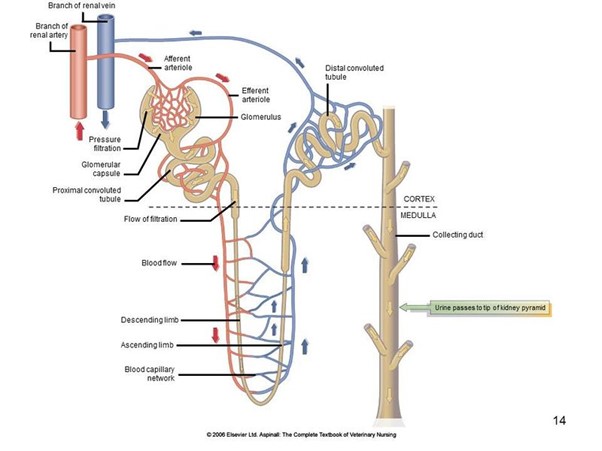

Below is a Nephron – otherwise known as the functional unit of kidneys. Kidneys are made of millions of these, and they determine how well a kidney functions. The classification of renal disease pertains to a disease or age related process affecting the function of the nephrons but does not necessarily indicate failure. Kidney / Renal failure describes when nephrons are damaged or overwhelmed and can no longer perform their normal function and failure ensues.

In this blog we will discuss different types of renal disease/ failure, diagnostics, classification, treatment and monitoring according to IRIS recommendations.

What is Renal Failure?

Renal failure (also referred to as kidney failure) can be caused by many conditions that negatively affect the health and functioning of the kidneys and its related organs.

A healthy animals’ kidneys work to regulate hydration, release hormones required to produce red blood cells, remove toxins and maintain a normal balance of electrolytes. If an animal experiences kidney failure, the kidneys no longer perform these functions efficiently.

While a diagnosis of renal disease may be scary, there are multiple treatment options that are proven to improve quality of life and likely extend it.

There are two types of Renal Failure:

Acute Renal Failure

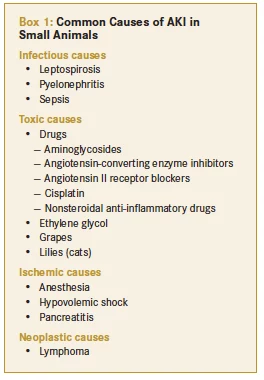

Most commonly associated with toxins or infections, acute renal failure causes kidney function to suddenly decline in hours or days.

Some common causes are listed in the box below, some are associated with better outcomes than others because they are treatable, or the cause can be removed. Unfortunately, most acute kidney injuries resulting in failure are still associated with a poor prognosis.

Chronic Renal Disease / Failure

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects an estimated 1% to 3% of all cats and 0.5% to 1.5% of all dogs. This type of kidney disease involves more gradual loss of kidney function over weeks, months, or years, and is irreversible. There are many potential paths to CKD, thus we will cover the more common causes:

- Age related decline is the most common, this can be potentiated by an acute insult at an early stage or an inherent susceptibility to renal degeneration.

- Chronic inflammation secondary to dietary or joint co-morbidities

- A stressed organ, such as heart disease, can result in changes in perfusion causing long term perfusion problems

- High blood pressure results in vascular damage causes parts of the kidney to be damaged over time

- Untreated hormonal diseases can result in metabolite deposits which can damage renal tissue.

- Neoplasia OR Cancer can grow within kidneys slowly damaging the functional cells over time.

Symptoms of Acute Renal Failure

Often these symptoms pertain to the cause of the renal failure:

- Fever due to infection or protein deposition

- Skin and gum ulcers in immune mediated disease or caustic toxin ingestion

- Neurologic symptoms, such as a wobbly gait or stilted gait in Ethylene Glycol intoxication

- Fresh blood or black tarry faeces – non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

Other more common symptoms include

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Weakness

- Inappetence

- Lethargy

- Abdominal pain ie. Prayer position

- Decreased temperature

- Foul breath

- Urination may vary from normal to very little or even none

- Seizures

Symptoms of Chronic Renal Disease / Failure

Signs of chronic disease can vary from subtle and slowly progressive to severe and apparently rapid in onset, they commonly include:

- Drinking too much

- Decreased in appetite

- Lethargy

- Overall weakness caused by low potassium in the blood

- Increased volume of urine in the bladder and therefore increased frequency of dilute urine (less yellow)

- Dental disease / bad breath

As Chronic renal disease progresses more symptoms will appear, such as:

- Vomiting

- Inappetence

- Significant weight loss

- Pale gums

- Ulcers in the mouth due to excessive urea in the blood resulting in bacterial overgrowth

- Bloody urine due to secondary infection

- Drunken behaviour or uncoordinated movement such as stumbling due to endogenous neurotoxins

If you pet has any of these symptoms, they should see a veterinarian urgently.

Diagnostic Work Up

The basic diagnostic work up requires blood tests, including SDMA, urinalysis and culture, abdominal ultrasound and possibly radiographs, if urinary stones are a suspicion.

With the minimum database collected we can assign an IRIS (International Renal Interest Society) stage and thereby treat minimally but effectively.

There are staging criteria for Acute Kidney Injuries resulting in ARF as well, but for the purposes of the Blog we will focus on CRD/F.

Please see the IRIS website for more details on AKI.

Grading of AKI iris-kidney.com/guidelines/grading.html

IRIS Staging in Chronic Renal Failure Patients

The elevation of blood waste product and abnormalities in urine, including the presence of protein, can indicate the severity of chronic kidney disease.

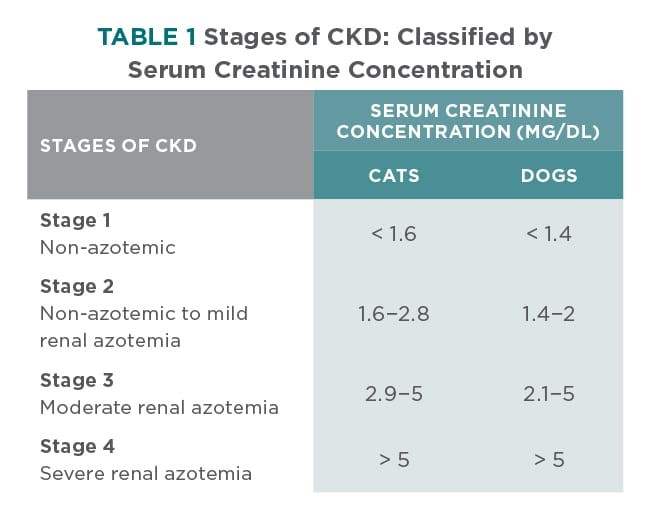

According to IRIS, stages of chronic renal disease are numbered 1 through 4 (with four being the most severe). The higher the stage number, the more symptoms you’ll often see in your pet. It’s best if some treatments are started when the pet is at a specific stage of chronic kidney disease.

Median survival time for dogs in Stage 1 is more than 400 days, while Stage 2 ranged from 200 to 400 days and Stage 3 ranged from 110 to 200 days. Stage 4 kidney disease ranges from 14 to 80 days, according to IRIS.

Using Creatinine For Staging

The IRIS staging system is based primarily on serum creatinine concentrations (Table 1). Serum creatinine concentration is a relatively insensitive marker of renal function and, therefore, dogs and cats with serum creatinine concentrations near the upper end of the laboratory reference interval may have decreased kidney function. Serum creatinine concentrations must always be interpreted in light of the patient’s muscle mass, urine specific gravity, and physical examination findings in order to rule out other causes of azotaemia (increased urea and creatinine).

To convert from mg/dl to micromole/L multiply by 88.4

The IRIS stages of CKD are primarily defined by serum creatinine concentration (Table 1) and then further categorized by:

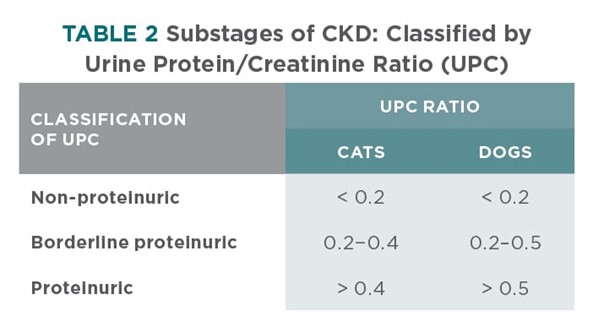

Renal Proteinuria / Protein in the urine

Renal proteinuria can be glomerular and/or tubular in origin (ie, excessive filtration, decreased tubular reabsorption, or both).

Renal proteinuria is persistent—with at least 2 positive tests separated by 10 to 14 days—and associated with inactive urine sediments.

Proteinuria is an important risk factor for the development of azotaemia in cats and the progression of azotaemia and decreased survival in both dogs and cats. Presence or absence of proteinuria is used to substage CKD (Table 2) in the IRIS staging system.

Systolic Blood Pressure

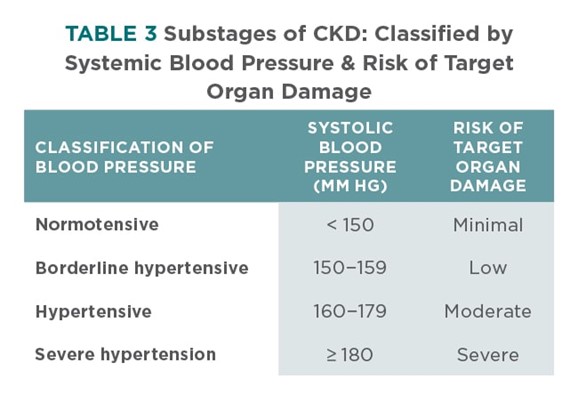

IRIS blood pressure sub-staging is based, in part, on risk of target organ—eye, brain, heart, and kidney—damage (Table 3). In the absence of target organ damage, persistence of hypertension should be documented.

Systolic blood pressure is typically measured by the Doppler methodology in dogs and cats.

SDMA Concentrations

Interpretation of serum symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) concentrations, along with serum creatinine concentrations, may increase the sensitivity for early diagnosis of CKD.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH AFTER STAGING

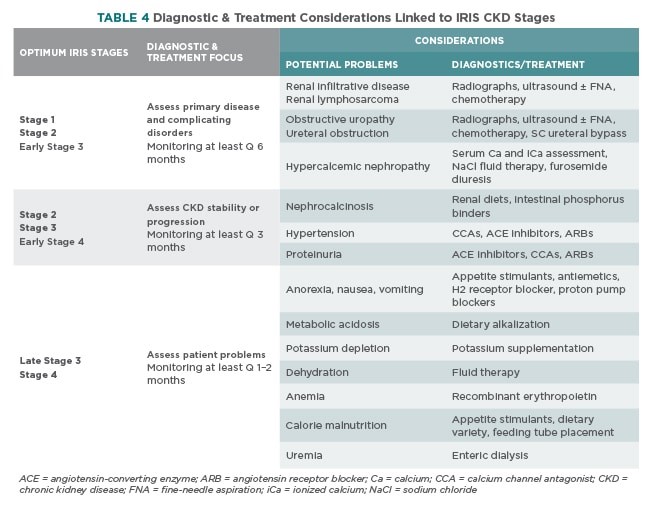

In general, the diagnostic approach to a patient once CKD has been identified and staged focuses on 3 areas (Table 4).

- Characterization of driver of the renal disease and/or complicating disease processes.

- Characterization of the stability of renal disease and function.

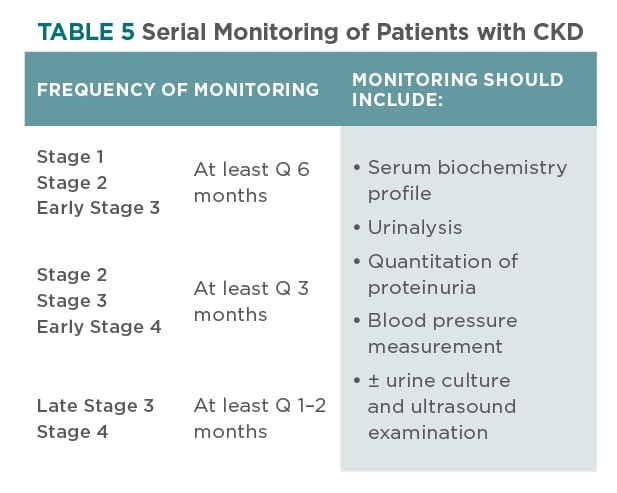

Stability of renal function should be assessed by serial monitoring of abnormalities identified during initial characterization of the renal disease (Table 5) - Characterization of patient problems associated with decreased renal function. Patient problems associated with decreased renal function (Table 4) may include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, dehydration, acidosis, potassium depletion, and anaemia.

Timing of Diagnostics

In the early stages of CKD, characterization of primary renal disease and/or complicating disease processes, as well as determining disease stability, are most important—when appropriate treatment has the greatest potential to improve or stabilize renal function.

In the later stages of CKD, characterization of patient problems becomes more important—when clinical signs tend to be more severe. In these later stages, diagnostic and subsequent therapeutic efforts should be directed at patient problems.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH TO CKD

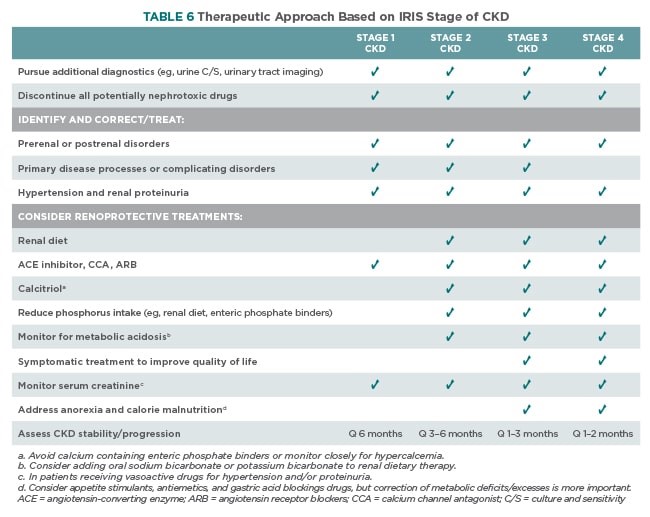

Therapy Tailored to CKD Stage

Similar to the diagnostic approach, the therapeutic approach to CKD should be tailored to each individual patient and that patient’s stage of disease (Tables 4 and 6). Serial monitoring of the patient—after treatment has been initiated—allows the clinician to change the treatment based on patient response (Table 5).

Renoprotective Treatments

- Dietary change designed to reduce serum phosphorus concentrations and decrease soft tissue mineralization

- Potentially Fortekor, Amlodipine or Semintra to normalize systemic and intraglomerular blood pressures and reduce proteinuria

- Potentially, calcitriol/ Vitamin D supplementation.

Amlodipine is typically the first line of defence for moderate to severe hypertension in cats, while ACE inhibitors are typically the first line of defence for hypertension in dogs as well as proteinuria in dogs and cats. Additional medication may be required if BP or proteinuria are refractory to therapy.

Phosphorus Reduction

Reduction of phosphorus intake is a major treatment goal for dogs and cats with Stage 2 and beyond CKD. The first line of defence against higher serum phosphorus concentrations is a gradual transition to a renal diet. A gradual transition over several weeks from a maintenance diet to a renal diet helps avoid any aversion to the renal diet.

Most renal diets are not only phosphorus restricted but:

- Contain reduced amounts of protein and salt

- Are supplemented with omega-3 fatty acids

- Are alkalinized to help offset the metabolic acidosis associated with CKD.

Feline renal diets are also often supplemented with potassium.

Enteric phosphate binders are the second line of defence if serum phosphorus is > 4.6 mg/dL / 0.25mmol/L after dietary phosphorus restriction (see Treatment Goals). Many different enteric phosphate binders exist but all need to be well mixed with the diet or administered at the time of feeding.

To increase efficacy, the binder should be in the gut when phosphorus from the diet is also there. The dose of the binder required to meet the target serum phosphorus goal will vary with the amount of phosphorus being fed and the stage of CKD.

In Conclusion

Kidney disease can be managed and treated relatively well, unfortunately with renal transplants and dialysis being inaccessible or cost prohibitive, our best chance at assisting is early diagnosis and proactive follow ups. For more information see the IRIS website for details

Staging of CKD : iris-kidney.com/guidelines/staging.html